PROFILE

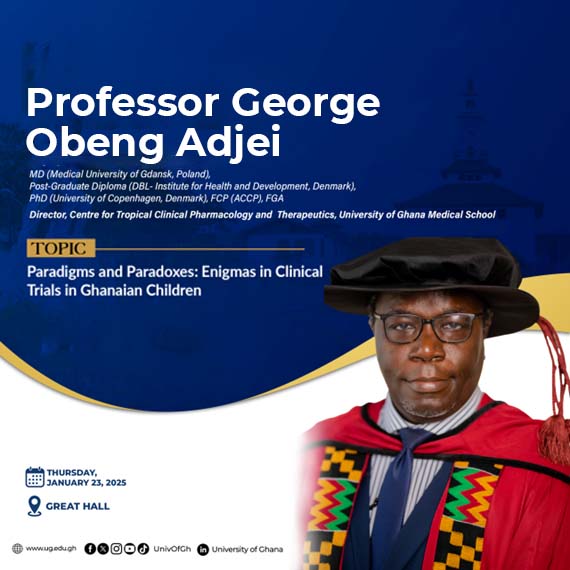

Professor George Obeng Adjei is a Professor of Paediatric Clinical Pharmacology at the University of Ghana Medical School. He has over 25 years of experience in clinical research and medical practice. He is presently the Director of the Centre for Tropical Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. He previously served as Director of Research at the Office of Research, Innovation and Development (ORID). Prior to joining University of Ghana in 2008, he worked as a medical officer at the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH).

Education

George Obeng Adjei started his primary education at Mampong-Akuapem and Akim Oda Presbyterian Primary Schools. He attended Koforidua Secondary Technical School for his GCE (General Certificate of Education) Ordinary Level and Advanced Level examinations, after which he served as a science teacher at the Larteh-Akuapem Presbyterian Secondary Technical, and Roman Catholic Junior Secondary Schools, for his one-year national service. He then proceeded to study medicine in Poland. Professor Obeng Adjei has an MD (medical doctor) degree from the Medical University of Gdansk (MUG), Poland; a postgraduate Diploma in Research Methodology, from the Institute for Health and Development, Denmark; and a PhD from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. He undertook post-doctoral fellowship training in affiliation with the Centre for Translational Medicine and Parasitology, and Department of Clinical Microbiology, Copenhagen, Denmark. He is a Fellow of the American College of Clinical Pharmacology. During his undergraduate medical training, Obeng Adjei developed a keen interest in Immunology and successfully combined housemanship training with hands on research on the genetic polymorphisms of the cytokine, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), in an experimental oncology research group then working on the anti-cancer effects of TNF, at MUG. As a resident medical officer at the Department of Child Health, KBTH, he was assigned additional responsibility to oversee the recruitment of patients into then-ongoing research on the pathogenesis of severe malaria in children. This opportunity offered him in-depth insights into some of the intersecting challenges and enduring gaps in childhood malaria treatment; experience that contributed to a shift of his research focus and career trajectory from Immunology to Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

Areas of Expertise and Research Highlights

Professor Obeng Adjei has expertise in several clinical, laboratory and field research areas. His research focuses on the applications of clinical pharmacology methods (pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics pharmacogenomics) within the context of clinical trials, to address questions of therapeutic relevance. He has conducted clinical trials that have provided insights into issues of long-term drug safety and efficacy, and implementation issues concerning the deployment of artemisinin combination therapy and antimicrobial-adjunct therapy in children. He has applied the novel population pharmacokinetic modelling approach to characterise antimalarial and antimicrobial drug disposition in newborns and children; studies that have made recommendations that have resulted in dosing modifications in clinical practice. Aspects of intervention studies he is presently overseeing focuses on evaluating the effect of nutraceuticals (natural polyphenol-rich cocoa) on outcomes in diabetes mellitus. He has also supervised trials that have evaluated the safety and efficacy of combination drug treatments for refractory pruritus (itching) - one of the major symptoms hindering recovery of patients suffering from burns. In more recent times, he has been exploring the application of precision medicine in the diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases within the context of multiple long-term health conditions (multimorbidity). Prof. Obeng Adjei’s research has resulted in over 100 publications in the form of articles in scholarly journals, book chapters, peer-reviewed conference abstracts and technical reports. His research has been published in some of the leading, reputable journals in his field such as Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, BMC Medicine, Clinical Infectious Diseases, and Lancet Infectious Diseases. Outcomes of his research have contributed to the evidence that was used to support a change of national antimalarial drug policy in Ghana, and to recommend a revision of facility treatment protocols for newborn infections at the KBTH. The data from his antimalarial clinical trials are part of the WWARN (WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network) database – and continues to be used to aggregate data for treatment optimization, safety monitoring and resistance tracking at the global level. Aspects of the collaborative research he has been part of have demonstrated the role of targeted community-based interventions in diagnosis and treatment of malaria in hard-to-reach, rural areas of Ghana. Other intervention studies in urban settings have demonstrated the role of adjunct physical exercise in conjunction with standard medication on outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Research Grants and Funding

Professor Obeng Adjei’s research has attracted funding from several agencies and funding institutions, both locally and internationally. He has been involved in multi-year collaborative research projects as principal investigator or co-investigator. He has been co-investigator of research projects funded by the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI-Ghana), French Expertise Internationale (FEI), National Institutes of Health (NIH), USA), Pasteur Institute (France), Sanofi-Aventis Recherche and Development (Sanofi-Ghana), and World Health Organisation (WHO). His work has obtained long-term DANIDA (Danish International Development Assistance) support spanning nearly 20 years. These include a competitive RUF (Danish Council for Development Research), PhD fellowship grant (2004-2007); a competitive FFU (Strategic Committee for Development Research) Post-doctoral fellowship grant (2010-2012); and a capacity development BSU (Building Stronger Universities) grant, spanning 10 years in three phases (Phase I, 2011-2013; Phase II, 2014-2016; and Phase III, 2017-2023). He is presently principal investigator of a collaborative research with funding from COCOBOD Ghana (through the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences). He has also received operational funding support (2006-2007) from the National Malaria Control/Elimination Programme (Global Fund for TB, Malaria and AIDS), and funding from the UG Research Fund (UGRF). Prof. Obeng Adjei has attracted private industry funding to the University from successful commercialization of UG-developed technologies, through his oversight responsibilities of the Technology Transfer and Intellectual Property services portfolio during his tenure as Director of Research, ORID.

Teaching, Training and Mentorship

Since his appointment as faculty member at UG, Professor Obeng Adjei has taught courses at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels in the Medical School, School of Pharmacy, School of Public Health, School of Nursing, and School of Biomedical and Allied Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences; and in the School of Veterinary Medicine, and West African Centre for Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens (WACCBIP), School of Biological Sciences. He has supervised postgraduate students at Masters and PhD, levels, as well as dissertations for the award of fellowship for the FGCPS (Fellowship of the Ghana College of Physicians and Surgeons) and FWACP (Fellowship of the West Africa College of Physicians and Surgeons) qualifications. He has supervised two post-doctoral fellowship projects and two of his former students have already attained professorial rank at UG. The first UG PhD student he supervised was awarded the best thesis in the Sciences for the 2015/2016 academic year. Prof. Obeng Adjei has supported and mentored many young faculty at UG. He has provided mentorship support and training opportunities in his research laboratory to several cohorts of PhD students. He serves as a tutor (in-loco parentis) in the medical students’ hostel, Korle Bu and has supervised and examined undergraduate medical students’ dissertations towards the award of the MBChB degree. Prof. Obeng Adjei has served as internal examiner of postgraduate theses at UG, external examiner of PhD theses for University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ghana and Universities of Cape Town, KwaZulu Natal, and Pretoria in South Africa. He has also served as an assessor of scholarly works for faculty promotions at both UG and external universities.

Boards, Committees and Extension Service

Professor Obeng Adjei has served on over 40 boards, committees and taskforces in the University of Ghana, including Academic Board, Business and Executive Committee, Colleges Research Boards, Intellectual Property Committee, ORID Management Committee, and School Management Committee of the Medical School. He has also served on several ad-hoc committees including search panels for appointments to senior administrative positions. Outside UG, Professor Obeng Adjei has served on committees at the national and international levels, including the Research Coordination Committee on COVID-19 (Ghana Health Service), Technical Experts Committee of the National Antimalarial Medicines Review Policy (National Malaria Elimination Programme), Scientific Committee of the National HIV/AIDS Research Conference (Ghana AIDS Commission), and National Steering Committee on Better Medicines for Children (Ghana National Drugs Programme/Ministry of Health). He has a passion for research ethics, especially the ethics of clinical research in children. He is the chairman of the Scientific and Technical Committee of the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital Institutional Research Board. He also serves as the chairman of the Ethics Committee, Radiological and Medical Sciences Research Institute, Ghana Atomic Energy Commission. He is an advisory board member of the Ghana Research Ethics Consortium and a member of the Ethical and Protocol Review Committee (CHS) and UGMC Research Ethics Committee.

Professional Associations and Consultancies

Professor Obeng Adjei is actively engaged in professional associations. He has previously (2008-2009) served as Temporary Advisor of the TropIKA.net knowledge management platform (WHO/TDR). Since 2010, he has been a steering committee member of the Developing Countries and Governance sub-committees of the International Union of Pure and Applied Pharmacology. He served as a member of the WWARN consensus committee that developed guidelines and standards for reporting pharmacokinetic studies of antimalarial drugs. In 2019 – 2021, he served as a member of the regional advisory board of the World Conference on Pharmacometrics. He is presently a member of the Observer section of the Global Malaria Policy Advisory Group (WHO). He is also a member of the Education Committee of the American College of Clinical Pharmacology. Professor Obeng Adjei has served as a consultant for Symbios (a private biotechnology company) and provided technical advice to research organisations and pharmaceutical companies. He is an advisory board member of the global pharmaceutical company, Novartis on infant malaria, and consultant/principal investigator for Azidus, the first bioequivalence company in West Africa. Earlier on in his career he provided additional clinical service at the childrens’ clinic, Amasaman General Hospital. Prof. Obeng Adjei was inducted into fellowship of the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences (GAAS) in 2019. He was elected a member of Council and Honorary Secretary of GAAS in 2024.

Family

Professor Obeng Adjei hails from the Adabiri clan of Ahenease in Larteh-Akuapem. He is married to Grace-Imelda, a consultant anaesthesiologist and critical care physician. They are blessed with four daughters: Odeisi, Adjeibea, Akwaaba and Asabea. He worships at the Asbury Dunwell Church, Accra, where he served as a member of the governing council (2018- 2021). His favourite pastime is gardening.

ABSTRACT

Paradigms and Paradoxes: Enigmas in Clinical Trials in Ghanaian Children The tenets of evidence-based medicine mandates that medicines should be tested and shown to be safe and effective before licensing for use in the general population. Clinical trials remain the recognized methods for evaluating safety and efficacy of medicines. Conducted in three overlapping phases, a clinical trial may be defined as “a research study in which one or more participants are prospectively assigned to one or more interventions to evaluate their effects on health related biomedical or behavioural outcomes.” While medicines licensed for use in adults would be expected to have undergone evaluation through all three phases (except in specific situations), this may not be so for children. There is evidence to show that many medicines used for treatment in children are prescribed outside the terms of their product license in terms of dosing, indication, route of administration etc. This phenomenon, termed “off-label drug use,” is a legal and acceptable practice, especially in situations when alternative treatments do not exist. It is also a means to respond to a specific patient’s medical needs. The practice of off-label drug use, however, bypasses the safeguards of modern drug regulatory norms and has been linked to an increased risk of adverse effects of medicines. Off-label drug use also occurs in adults; however, it is typically based on new evidence that demonstrates the safety and efficacy of medicines for new indications. In children on the other hand, off-label drug use is often based on extrapolation in the absence of firm evidence. Thus, medicines that have been tested in and found to be safe and effective in adults but not tested prior to use in children would not be supported by the same level of high-quality evidence. This has the potential to perpetuate an anecdotal belief system and risk a false sense of assurance that does not encourage further rigorous testing, thus depriving children of high quality evidence on medicines. The relative absence of information on medicines in children was an unintended outcome of regulation intended to enhance drug safety. Outrage from the infamous disasters resulting from unintended but improper medication use in children resulted in landmark legislation such as the Pure Food and Drug Act, 1906 (enacted to prevent adulterated and misbranded drugs from entering the market) the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act 1938 (enacted to ensure (for the first time) that medicines demonstrate safety and purity before marketing); and Kefauver-Harris Amendments 1962 (to ensure medicines demonstrate efficacy in addition to safety). Drug manufacturers resorted to including warnings in labelling to the effect that these medicines “were not recommended for children due to inadequate (or non-existent) data, and strategic decisions to exclude children from clinical trials of new medicines following passage of these laws. Advocacy to the effect that lack of information on medicines in children was encouraging off-label practice and that treating children with untested medicines should be likened to uncontrolled experimentation and thus, potentially unethical, may have contributed to the establishment by the (US) National Institutes of Health (NIH), of the Paediatric Pharmacology Unit (PPRU) network (in 1994). The mandate of the PPRU was to stimulate collaborative research between academia, industry and healthcare providers to improve paediatric labelling of new and existing medicines. Subsequent legislation introduced from 1997 with a focus on initiatives and incentives like assurances of patent exclusivity for paediatric studies and labelling change mandates opened the space for paediatric medicines research subsequently. It was during the years when research on paediatric medicines were being encouraged that I began participating in and subsequently led and supervised several clinical trials with the overall focus to improve drug therapy in Ghanaian children. These trials investigated issues contemporary to the times, including studies in sub-populations with high morbidity and mortality, childhood populations recognized for lack of data on most medicines (such as newborns), or evaluation of the then novel drug combinations. Specific examples include trials to evaluate efficacy of quinine preparations in children cerebral malaria; artemisinin combination therapies in children with uncomplicated malaria, HIV infection or sickle cell disease; amikacin (an antibiotic) and aminophylline (a drug used to improve breathing in newborns) combination in newborns with sepsis; and cetirizine (antihistamine) and gabapentin (an anticonvulsant) combination for treating pruritus (itching) - a common disturbing symptom that compounds the affliction of patients recovering from burns. Aside efficacy, our studies sought to generate evidence on relevant safety parameters, with a special focus on investigating “what the body does to medicines” in terms of their movement in and out of the body (i.e., absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion) – otherwise known as pharmacokinetics (PK), and overall mechanistic effects of the respective medicines on the body - otherwise known as pharmacodynamics (PD). To overcome the clinical, logistical and ethical limitations of repeated multiple blood sampling required for conventional PK studies, which historically discouraged children from participating in PK/PD studies, we applied the novel (population) modelling approach that requires only 1-2 blood samples per patient to enable us to characterize the PK/PD profile of studied medications. Beyond biomedical outcomes and in the spirit of multi- and inter-disciplinarity, our studies incorporated strong socio-cultural components to gain insights into relevant contextual factors. In collaboration with sociologists and bioethicists, we interrogated issues like the adequacy and appropriateness of informed consent procedures, parents’ perspectives of their child’s recovery from study medications and their views on the appropriateness of use of blood samples for further research. Children are not small adults, and childhood is composed of a heterogeneous population. Children exhibit distinct developmental, maturational and physiological characteristics that differ from adults. Even the practice of scaling adult drug doses for children using body weight or surface area may be inappropriate because these are based on allometric scaling but human growth is not a linear process. There are also discordant age-associated differences in body composition and organ function at certain stages of growth that should be integrated into other considerations. There are still critical gaps in knowledge on the role of maturational and ontogenic changes in drug disposition in children and there is still a lack of full understanding of the effect of these changes on drug metabolism. There is the need therefore, for comprehensive research on many old as well as new medicines used for treatment in children. This would require an intentional, comprehensive child centred paradigm. In this inaugural lecture, I will present a synthesis of the findings from the various studies and discuss their relevance and implications for clinical practice and policy where applicable. I will also highlight unexpected findings that were deemed inconsistent with our hypotheses or conventional assumptions and share insights from the encountered operational challenges. I will also seek to interrogate these findings in the light of drug regulation in Ghana and share my perspectives on capacity needed to be developed strengthen the medicines research architecture to improve drug therapy for children in Ghana.